|

For more information visit The Polish submarine Orzel: Legend of WWII

by Miltiades Varvounis

A little more then sixty years ago, on the 10th February 1939, a crowd of many thousands welcomed Poland's most modern submarine the Orzel, at Gdynia, as she was arriving at her home port, from the Dutch yard Koninklijke Maatschappij "de Schelde" at Vlissingen. The warm and enthusiastic reception given to the submarine, named after Poland's national emblem was, in the face of a threatening war, the expression of feelings cherised by the population of Gdynia, and of the coast in general, for the youngest representative of the Polish Navy. It must, moreover, be noted that the ship, representing at the time the last world in naval technique, was built from fund raised from spontaneous and voluntary contributions on the part of the Polish community, who desired in that way to help the State in arming Poland. The magnanimity of the gift offered by the Polish community, on behalf of its young Navy, was a venture on a scale unheard of in contemporary naval history. Subsequent events proved the sacrifice to have been well worth while: in the course of the war instigated by the Nazis, which broke out shortly after, the Orzel covered herself, and the Polish flag, with everlasting glory.

The Orzel, ordered on the 29th January, 1936, was launched on the 15th January, 1938, and a year later, at the beginning of February, 1939, she arrived at Gdynia to take up service with the Polish Navy.

| | Orzel arriving at Gdynia |

She was a large ocean-going submarine of 1 110/ 1 473 tons displacement, 19 knots surface speed and 10 knots submerged. She was equipped with one 105 mm gun, two 40 mm anti-aircraft guns and twelve torpedo tubes. Her crew numbered 6 officers and 54 petty-officers and ratings. Like the rest of the Polish submarines, the Orzel remained at sea as from the outbreak of war, and her situation was rather hopeless, in view of the enemy's enormous predominance on the seas as well as in the air. Later on, the commander's illness and damage to the ship herself, caused the Orzel to call at the neutral Estonian port of Tallinn. It was then that events began to race ahead, like an excerpt from a thriller, or adventure film. Against the rules of international law, the ship was interned by the Estonians, doubtless under pressure from the Nazis. Cherts, navigation instruments and major part of her armament (fourteen of the twenty torpedoes, munitions, gun breech-blocks and small arms) were confiscated. In spite of the Orzel having been hauled into an interior dock, where she was moored to an Estonian gunboat, her commanding officer, lieutenant-commander Jan Grudzinski decided on escape. It was as if no power on earth could stop the Polish seamen in their instinctive love of freedom. On the 18th of September, at three in the morning, the Orzel broke loose from Tallinn.

She set out on her month-long odyssey in the Baltic. There were no charts on board, but the navigator, sublieutenant Marian Mokrski drew them extempore, with a list of light-houses and a Baltic Pilot book on hand. Helped by those charts the Orzel hunted German ships and went through many a further adventure, tracked both at sea and in the air, by enemy forces attracted by the news of her escape. In spite of the threat of eventual discovery, the Orzel came up to the coast of Gotland, where she landed two Estonian guards, who had been on board at the moment of her escape from Tallinn. As the supplies of food and fresh water were rapidly running short, the decision was taken on the 6th October, to make for Great Britain through the Danish straits, in order to join the allied naval forces.

| | Orzel in Rosyth |

The venture was a success in spite of minefields, enemy patrols in the air and on the sea, in spite also, of the lack of accurate charts. The Orzel past the Sund and after lying quiet for a while in the waters of Kattegat and Skagerrak, crossed the North Sea and arrived at Rosyth. Allies and enemies alike, agreed that the Orzel's military and navigational achievements "had no equal in naval history". The French gave the Polish ship the nickname "le sous-marin fantôme", i.e. the phantom ship. Not even Mr. Goebbels propaganda -one-sided and full of hate against everything Polish as it was - could hush up the fact that the ship "in eluding her captors, had avoided internment in Tallinn, then, leaving behind her confiscated charts and armament and after an adventurous and military point of view - reached the British coast".

On the 14th October, 1939, the Orzel arrived in Great Britain, where she met another Polish submarine Wilk, which had passed the Sund and joined the Royal Navy three weeks earlier. The Orzel was first directed to the Caledon Shipyard at Dundee for refit. There she was visited by the Polish prime minister general Wladyslaw Sikorski and commander-in-chief Polish Navy, admiral J.Swirski.

In December 1939, the ship joined the second Submarine Flotilla at Rosyth (the Wilk also), where she received on board, a liaison staff consisting of one officer, one signalman and one telegraphist from the Royal Navy.

With both her guns useless, the breech-bloks having been taken away by the Estonians, and with her torpedo tubes not adapted for the British torpedoes, the Orzel was employed in escorting convoys in British waters exclusively, at first. At the end of December, she was on convoy duty to Bergen in Norway, and from the middle of January 1940 on, took up independent patrolling. Her first patrol off the coast of Norway, and two subsequent ones in February, in the southern part of the North Sea, were fruitless, as no enemy ship was sighted.

The Orzel's next assignment, was patrolling the region of Stavanger (south of Bergen). On this occasion she met a Danish freighter. On her fifth patrol, the Orzel left Rosyth on the 3rd of April and made her way towards the southern coast of Norway. There, on the 8th of April, she met the enemy.

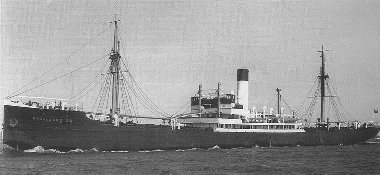

| | German troop ship Rio de Janeiro |

It was the German troop ship Rio de Janeiro (5 261 GRT), transporting - as was later discovered - invasion troops to Norway. According to international rules, lt-cmdr J.Grudzinski requested that the transport stop, and her captain come on board the Orzel with his papers. As the Germans failed to do so immediately, the Orzel fired a torpedo, which hit the target. The German vessel sank, Norwegian fishing craft rescued a number of German soldiers, prematurely revealing thereby, the German invasion plans. Unfortunately, neither the Norwegians nor the British were in a position to prevent the invasion.

On the 10th of April, during the same patrol the Orzel attacked, one of three German trawlers she met.

[That day Orzel attacked auxiliary minesweeper V 706 (278 BRT) but missed it - ASB]

The next day, the Polish ship tracked a large enemy transport, but her attempt at attack was frustrated by an enemy plane. For the next four days the Orzel was pursued by German trawlers, E-boats and aircraft, but she withstood all attacks and safely ended the patrol on the 18th April.

[On 11.IV.1940 Orzel while attacking German troop ship Itauri (6 838 BRT) was spotted by the escort and forced to withdraw - ASB]

The next patrol, from 25th April to the 11th May, brought no result. Then there was the seventh patrol, on which the Orzel sailed on the 23rd of May. She was sent to the central region of the North Sea, did not sight any enemy vessels, so on the 1st and the 2nd of June a wireless message was sent from Rosyth to the Orzel, with an order to change her patrol area and proceed for the Skagerrak. No signals had been received from the Orzel since her departure and on the 5th of June the order was sent for her to return. She failed to acknowledge reception of this signal (as well as the other signals) and she never came back to Base. The 8th of June, 1940, has been officially accepted as the day of the Orzel's loss.

What happened to Orzel? She has still not been found, but there are two possible explanations.

The Admiralty stated in 1962 that Orzel had been lost in a British minefield at 57'00N/03'40E on 25 May. That minefield had only recently been laid there, and it was admitted that it had not been possible to inform all of the Allied ships, including Orzel, about the existence of that new minefield. (Presumably it was not possible to inform ships which were already at sea when the minefield was laid). That Admiralty statement is held in the Public Record Office under Class Mark ADM 199/1925. It is also worth mentioning that British acoustic stations heard a loud noise that day, which was assumed to have probably been something hitting a mine.

The date of loss might have been 8 June. When Orzel was returning to Rosyth she might have hit a mine in a new German minefield, 16B, which was located near the British minefield. The Allies were unaware of the existence of minefield 16B at that time, and it was considered very likely that the Dutch Submarine O-13 was lost in that minefield five days later. The location of this and some other German minefields were not known until German charts were captured with Enigma material during the Combined Operations raid to the Lofotens and Maaloy in capture a German weather reporting trawler known to be north-east of Iceland carried out on 7 May 1941.

from "The story of the Orzel" J. Pertek

|